Posted on January 20, 2022 by Tracy Hester

Beachcombers in Galveston has been seeing ghosts of a biologic sort. For nearly a decade, wild dogs that vividly resemble endangered red wolves have begun to appear in the Texas coastal plain. While these canids officially count as coyotes – a nettlesome varmint to many Texans – their spectral appearance has sparked local excitement because the wild dogs contain a genetic shadow of their endangered forebears who disappeared from the Gulf Coast long ago.

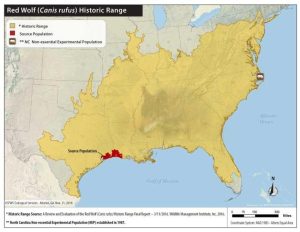

Red wolves have a problematic, and tragic, history under the Endangered Species Act. Red wolves are striking animals that historically hunted and roamed over large swaths of the southeastern United States. Broad habitat loss and aggressive state-sponsored hunting and trapping campaigns drove the red wolf to the brink of extermination, and the species was declared extinct in the wild in 1980. The U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service took desperate measures in 1990 to save the wolf by effectively extirpating it. The Service tracked down the hardiest examples of the species (in a fashion that many critics felt winnowed out other viable wolves), captured several in Texas, and relocated them to a secured habitat in North Carolina. This drastic measure effectively wiped out red wolves everywhere else in the United States. And, unfortunately, that altruistic relocation has had mixed results, at best, in restoring the red wolf population. Red wolves are now listed as critically endangered by the International Union for Conservation of Nature, and as of October 2021 only eight (8) were known to remain in the wild in North Carolina.

As a result, the appearance of wild dogs that resemble red wolves in Galveston has stirred hope that the species may re-establish a foothold. The dogs themselves, unsurprisingly, have proven elusive. But genetic analysis of skin and blood from road fatalities as well as of scat have shown that some of these wild canids contain a striking amount of red wolf genetic material: up to 55% in some cases. One sample even showed 100 percent red wolf ancestry.

The Endangered Species Act, for all of its sweep and power, is ill-equipped to handle this situation. Mixed breed animals like these wild canids have previously been considered hybrids, and regulatory efforts have typically centered on how to prevent hybridization from swamping the purity of genetic lines in endangered species. While debate has flared over how to incorporate cloning and other genetic technologies to protect endangered species or revive extinct ones through experimental populations, the Act and its regulations do not provide an obvious path to protect common animals that could contain important genetic echoes of disappearing species.

In some ways, these ghost wolves are genetic reliquaries: vessels that contain a crucial biological message to the future. We should decipher how to save and use this information to protect species that are fading away, or have already disappeared, from the wild. In the meantime, citizens groups in Galveston have begun to organize voluntary conservation efforts, and students at the University of Houston Law Center have provided pro bono legal assistance to help start new non-profits. Hopefully these increasingly popular observation programs will draw attention and resources to help save Galveston’s spectral packs.